Since 1937, the –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ Symphony Orchestra has been an essential presence the campus life and musical vibrancy of OCU University. Explore the –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ Symphony Orchestra's rich history through the articles, below.

Many thanks to Dr. Jake Johnson, Associate Professor of Musicology and Associate Dean, and Christina Wolf, Archivist & Special Collections Librarian for their invaluable contributions in discovering, archiving, and authoring these articles.

Clarence Burg (1893-1986) had an immense impact on the world of music education, especially in piano teaching. He began teaching private piano students at the age of 12. Programs from his early performances show that he was familiar with standard piano works by composers such as Mozart, Liszt, Chopin, and Debussy from a young age. After only a year of collegiate study, he founded the Burg School of Music, a piano-focused music school in Ft. Smith, Arkansas. Within three years, his program included over two hundred-fifty students and had to bring other teachers on board to handle the student load. He also started the Clarence Burg Music Camp‚Äďa summer program in the Arkansas Ozark Mountains. Burg was successful as a teacher, but was also heavily involved in performance and went on tour with the Metropolitan Opera in the fall of 1927.

During his tour with the Metropolitan Opera, OCU University trustees took notice of Burg in 1928 when Burg performed a concerto with the –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ Symphony Orchestra (the predecessor to the OKC Philharmonic) which was being conducted by Fredrik Holmberg, Dean of the School of Music at the University of Oklahoma. The OKCU trustees encouraged him to apply to fill the opening for Dean of the College of Fine Arts, and Holmberg encouraged him to take the position. He was elected Dean in June of 1928 and started work on the first of July. Dean Burg expressed interest in the up-and-coming nature of –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ itself. He saw a lot of room for the city to grow, and he planned on leading the school in growth alongside the city.

Burg served as Dean of the College of Fine Arts from 1928 to the spring of 1962. Under his tutelage, the music school gained accreditation, added music degree programs, and an orchestra. When Clarence Burg became the Dean, the instrumental performance program only trained violinists. Through the prominence of the violin studio, Dean Burg founded the symphony. With origins as a string ensemble class, the OCU University Symphony Orchestra did not become a full orchestra until 1937.

Dean Burg conducted and performed on the inaugural concert of the OKCUSO‚Äďhe did not conduct the whole concert as he was also featured as a soloist. It is unclear how involved Dean Burg was with the orchestra after their first year when he handed the building of the ensemble off to James Neilson. After his work with the symphony, Burg continued his work as piano professor and worked to build his studio both inside and outside of OKCU. In 1962, Clarence Burg retired as Dean of Fine Arts, but he continued on as professor of piano for another twenty years.

© 2019 Jake Johnson

Though the OCU University Symphony Orchestra premiered its first concert under the direction of esteemed pianist and Dean Clarence Burg, the ensemble really came into its own under the direction of Dr. James Neilson. Neilson directed the symphony orchestra ‚Äď alongside multiple choirs and the university symphonic band ‚Äď from 1939 until the early 1960s when Ray Luke took direction of the ensemble.

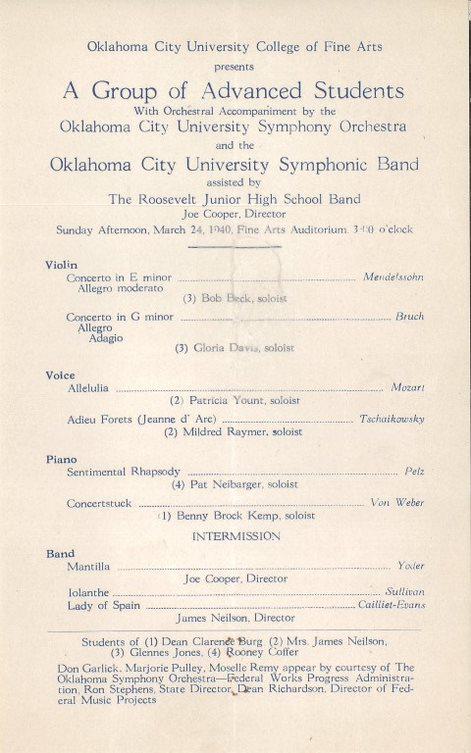

With Neilson at the helm, the orchestra came a far way from its lowly beginnings. Initially, it started as an ensemble seminar featuring opera overtures performed by the few string majors. Performances seemed to be largely consistent in content‚Äďprograms included works by major composers, such as Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, and Mendelssohn, as well as some more recent works by American composers. In 1943, the ensemble began performing in Commencement Services. They performed processional and recessional music by such notable composers as Saint-Saens and Grieg. The group also regularly performed the March from Arthur Sullivan‚Äôs Iolanthe. The piece was featured on various commencement programs as well as on the University Presidential Inauguration of Cluster Quentin Smith in 1942.

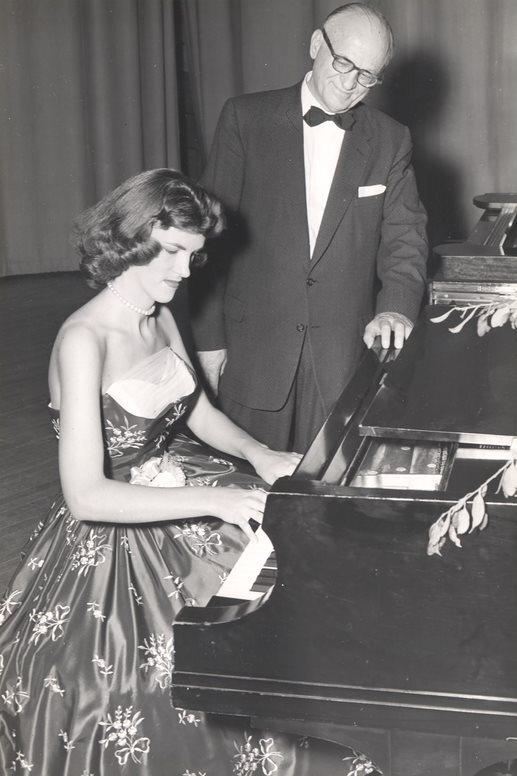

In addition to serving as the conductor of the orchestra, Neilson also began the ensemble’s tradition of having soloists perform concertos alongside the orchestra. Nearly every concert featured at least one faculty soloist; Dean Burg was featured regularly on piano. Once or twice a semester, the School of Music hosted a concert where students performed their pieces with the orchestra. The ensemble also frequently played alongside local high school ensembles.

Neilson also led the pit orchestra in the beginnings of the University’s rich musical theatre history. The ensemble played alongside performers in opera titles such as Pirates of Penzance, a Naughty Marietta, Amahl and the Night Visitors, and Martha among many others.

Dr. Neilson‚Äôs rich love for the classics was apparent in his programming. The ensemble often performed pieces by Bach, Handel, Brahms, and Mozart. He also featured lesser known composers, such as Paul Yoder and even pieces he composed himself ‚Äď often including his wife as a soprano soloist. He saw the value in new music and once invited Frank Skinner as a clinician and presented a concert featuring songs from major motion pictures. In the early 1960‚Äôs ‚Äď Ray Luke began as director of bands and programs stayed similar to those of James Neilson in that most of his programs consisted largely of major European composers, however his programs were more diverse. He most commonly programmed Beethoven, Bach, Wagner, Holst, and Debussy. Ray Luke‚Äôs programs occasionally included newer music like Leonard Bernstein‚Äôs On the Waterfront in 1968, only five years after its premier. Dr. Luke also featured pieces by 20th century composers such as Dmitri Shostakovich, Samuel Barber, and Aaron Copland.

© 2019 Jake Johnson

The –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ Philharmonic and the OCU University Symphony Orchestra share a lot of history, and both have grown considerably since the 1930‚Äôs. OKCU has seen many of its alumni go on to work with the Philharmonic, but records show that the OKC Philharmonic and OKCUSO are linked in more ways than shared personnel.

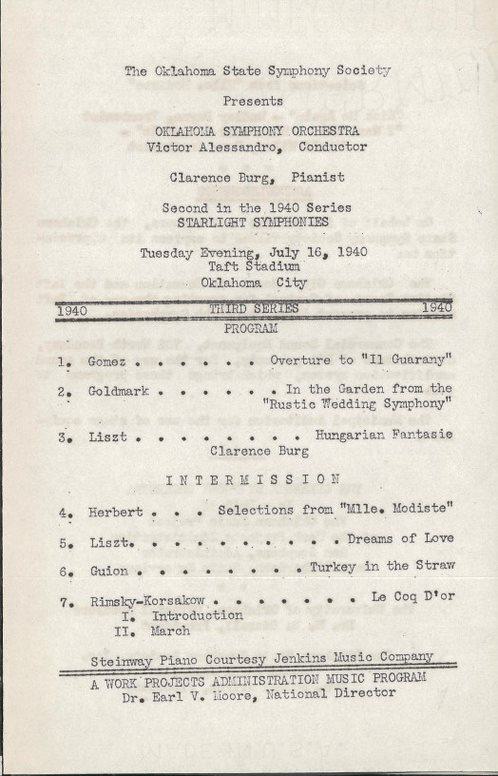

The early OKC Philharmonic used facilities at OCU University for their rehearsals and recordings before they found their home at the Civic Center in Downtown –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ. Programs from the 1940s suggest that OCU University hosted several concerts for the –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ Symphony Orchestra including one on July 16 of 1940 when Clarence Burg performed Liszt‚Äôs Hungarian Fantasie with the Oklahoma Symphony Orchestra.

The –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ Symphony Orchestra‚Äôs Final Broadcast of the 1951-52 season titled, ‚ÄúSalute to OCU University,‚ÄĚ featured faculty and students of the OCU University School of Music. The ties between OKCU and the Philharmonic did not end in the 1950s. In 1968, the OKCU Symphony Orchestra was under the direction of Ray Luke, who was also the Associate Conductor of the –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ Symphony Orchestra. These ties forged the strong relationship between the –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ Philharmonic and the OCU University Symphony Orchestra that we know today.

© 2019 Jake Johnson

With origins as a string ensemble, the OCU University did not become a full orchestra until Dr. Clarence Burg founded it in 1937. It is unclear how involved Burg was with the orchestra after their first year. Even as the first conductor Burg did not conduct the whole concert. Instead, he was featured as a soloist, playing Edward MacDowell’s Piano Concerto in D minor during the second half. The concert also featured Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte Overture, Schubert’s Symphony in B minor, the bacchanal from Saint-Saens Samson and Delilah, and they ended the program with Tchaikovsky’s Marche Slave.

At that point in time there was only an availability for people to study music at the collegiate level if they studied strings, piano, or voice. A wind instrument program was not added until much later. Even the orchestra started as a mere extracurricular activity that a group student could participate in for fun. Burg served as Dean of the College of Fine Arts from 1928 to the spring of 1962, and under his tutelage the music school gained accreditation, actual music degree programs, and an orchestra.

Clarence Burg‚Äôs focus at OCU University was originally to act as a recruiting tool, but as he spent time there, his focus shifted to music education, particularly in piano. Burg‚Äôs outreach contained his own summer music program hosted in Arkansas, a piano workshop for piano teachers across the state of Oklahoma, and a piano festival which at its peak was attended by over 1,200 students. Outside of his university students Burg also maintained a studio of young learners that often went on to study at –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ.

© 2019 Jake Johnson

Professor Parthena Owens has been the Professor of Flute at OCU University, where she received her Undergraduate degree in 1981, since 1989. In this interview, she discusses with MM Bassoon Performance Major Kevin Foss the influence that Ray Luke had on her music career.

Parthena: I was wondering if the recordings of the‚Äďit was called the ‚ÄėRay Luke retrospective‚Äô‚Äď if you‚Äôve found those. It was like several nights of‚Äď we just celebrated Ray Luke.

Kevin: Just going through all of his music? Was that recent?

P: Well, he was alive still. He had retired. But we went back through…

K: He hasn’t been gone for too terribly long, has he?

P: No, no it hasn’t been that long. But I had wondered, you know…. That was a huge showcase of his music.

K: That‚Äôs one thing I think we‚Äôve been curious about that has been hard to find is how much his music has actually been‚Äďespecially since he‚Äôs been not working here‚Äďhow much his music has been utilized and put into performance

P: Probably not a lot

įŕ‚Ķ.Ī’

P: When he passed away, four of us went to his house and his wife‚Ķ and his garage was full of boxes of his stuff. įŕ‚Ķ] We went through all those boxes and got it all put together to be donated and catalogued here.

įŕ‚Ķ.Ī’

K: įŕ‚Ķ] I‚Äôve got some basic questions just to kind of get us going‚ÄďHow did you know him? How did you know Ray Luke?

P: He was my orchestra, and band, and orchestration teacher here when I went to OKCU. And Pit orchestra.

K: He did everything

P: And he was composer in residence

K: So he was… that’s a lot of hats. …. I don’t know, I guess I’m a little astonished

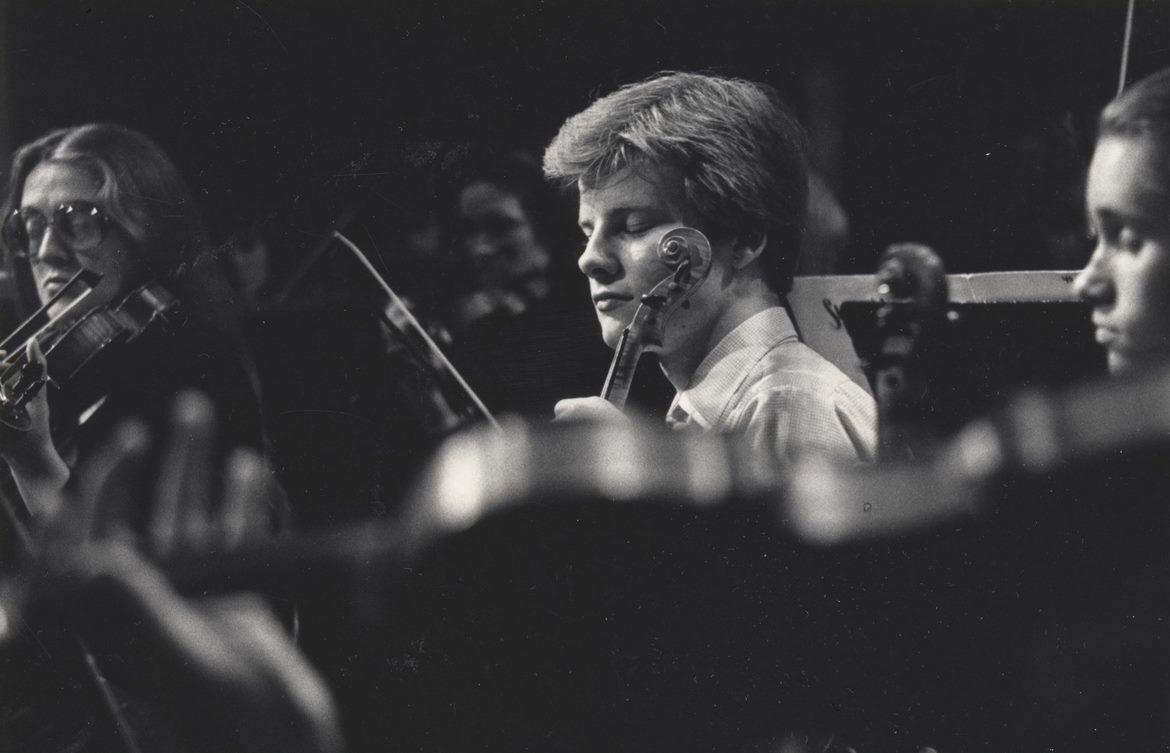

P: The orchestra at that time was not like what we have today. It was a community orchestra. We didn‚Äôt have the string program that we have now. So, people from the community came in and played‚Äďfilled in the string section.

K: What percentage would you say, if you were going to guess‚Äď like how many OKCU students versus community players? Or did we have a string program at all?

P: We, yes, it was just not large at all. It might have been even more than 50 percent community players in the strings.

K: Did they bring in players‚ÄďI know OKCU had a connection with the philharmonic or‚Ķ

P: The Oklahoma Symphony

K: The Oklahoma Symphony, before it was the Philharmonic

P: Dr. Luke conducted the Oklahoma Symphony for a season

K: Was it professional type players‚Äďwas it players from that group that would come in and fill in at OKCU, or was it more amateurs and friends of the school?

P: The teacher, Lacy McLarry, who was the concertmaster, taught here. He also came in. There were quite a few players that came in and out in the string section. And they had to hire strings to play the pit. They didn‚Äôt have to fill in too much with winds‚Äďevery now and then they would fill in maybe a horn or something. It only met once a week on Monday nights and that‚Äôs all it was.

K: How would you describe Ray Luke? Just as a person, as a teacher, how would you describe him?

P: He commanded respect. He was generous to a fault‚Äďif you did the work. I personally‚Äďand many in my generation that went to school here‚Äď kind of worshipped the ground he walked on, because he was that kind of person that if you worked for him, he gave you every opportunity in the world. Many of us are successful today, I truly believe this, because of the way he taught us and that kind of ethic.

K: Do you have any strong memories or stories that you feel kind of capture that? His essence or…

P: [laugh] I‚Äôve got lots of stories. But, for me personally, I call him a mentor. I was a junior here and we had‚Äďoh it was a great flute section. Ten, twelve top notch flute players. And my freshman and sophomore year I was kind of like, ‚Äėwow, all these players,‚Äô you know. But I was in orchestra, I was in everything, I just didn‚Äôt take it too seriously. My junior year is when he‚Äďwe did his opera that won all the national‚Ķ

K: Medea? We’ve been trying to find a recording of that one…

P: Ok. So I‚Äď it was my turn to play in the pit, and I didn‚Äôt know what I was playing, so I had to go to his office to get my part. And he said, ‚ÄėWell what part?‚Äô and I said, ‚ÄėI don‚Äôt know,‚Äô and he handed me first part and I was shocked. He said, ‚ÄėI‚Äôve been waiting‚Äďwaiting for you to ask,‚Äô but he said, ‚ÄėI‚Äôve decided you‚Äôre not going to,‚Äô he said, ‚Äėyou‚Äôre the one. You‚Äôre the one that‚Äôs gonna make it.‚Äô That‚Äôs why he gave me first part, and it changed my life.

K: This might be in a similar vein, but how did he impact the work that you do at OKCU now? Do you feel that he has an effect on the work you do?

P: I try to do things the way he did them. The way I was taught. You know, he [laugh] the little sayings he would‚ÄĒ like, ‚Äėif it‚Äôs a right note in the wrong place, it‚Äôs a wrong note.‚Äô And just how he expected everything to be learned‚Äďthat kind of thing. I guess that‚Äôs what I try to keep going, you know. The excellence.

K: The next question I had written down was what pieces do you remember working with him on‚Äďwhat pieces of his, but I guess there‚Äôs Medea, there‚Äôs the flute sonata‚Ķ

P: The flute sonata, the flute choir piece he wrote for us, the quintet we had performed when we had the faculty quintet. We did some band pieces, one that I remember vividly, ‚ÄėPlaints and Dirges‚Äô, because we called it ‚ÄėPlates and Dishes‚Äô [laugh]

K: What was it like working with him in rehearsal? Did he spend much time rehearsing you on his music, and what was…..

P: Yeah, we did quite a bit. He was a‚Äďa tyrant.

K: He knew exactly what he wanted?

P: He had a temper, he threw things. You didn’t want to get on his bad side. Yeah. [laugh]

K: Did he program his own music frequently when he was running the orchestra and the band? Was it a lot of his music or įŕ‚Ķ.Ī’ other new music, or was it a lot of standards?

P: It was the standards. We did the standards, and then when he had something we did it. But it wasn’t all the time by any means. We learned all the standard band literature and orchestra.

K: I think I’ve read some maybe interviews or something with him where he seemed to kind of have that common opinion, among composer-y folks especially, that it’s too much of the same old things and not enough of the new. Did he put in an effort, do you think, to program new music, or did he feel too much of the sort of expectation to do the standards?

P: I don‚Äôt remember doing too much new, except what he maybe wrote, or what Frank Payne wrote‚Äďwho was also here and composing. But it seemed like in orchestra, it was Wagner‚Ķ you know we did the big standards. I played in the orchestra after I graduated because things kind of started to tank here‚Äďwe weren‚Äôt getting numbers, and so for about three years after I graduated I came up here and helped out and played shows, and I was playing with the symphony at that time. I had to go ask [Ray Luke] if I could be payed. That was hard, to go in there. Because he was just such a formidable person, you know, it was hard to walk in his office and ask. And once you did it was fine, you know, but he was just that kind of‚Ķ he was up here and you were down here [laugh]

K: Do you think he still has an effect on OKCU as a whole today? Do you think that his legacy, his ideas, anything… or do you think he has sort of moved on and other people have filled the…

P: I don’t think that there’s anyone here who remembers him particularly. Mark Parker was here, Larry Keller, myself, that’s it. And so, no one else knows who he is.

K: So as much as he was‚Äďhe was the program‚Äďhe was running the band, he‚Äôs running the orchestra, he‚Äôs composing, he‚Äôs conducting, but it‚Äôs all moved on from that you think? There‚Äôs isn‚Äôt much of an imprint left?

P: I think so. And I think that he wanted that, of course. His protege here was Steve Coker, who took over the band kind of about halfway in my undergrad where Dr. Luke was just doing the orchestra and composing, and he had some health issues so Coker took over the band and he did band and choir‚Äďall the choirs. So, his legacy kind of went to Steve. But I think there‚Äôs enough of us out there around‚Äďwe all think the same thing of Dr. Luke. He was just‚Ķ god to us, you know? And you know his Son has tried to keep things going too

K: Yeah, we have contact information for him. We might reach out for an interview įŕ‚Ķ] Well that‚Äôs all I really had written out, it‚Äôs a pretty brief interview. But do you have just any other thoughts or anything about him that you feel is worth preserving for this?

P: hmm. Well, you know you hear the stories of Ray Luke, of him being that tyrant and that temper and the demand for what he wanted, but he was also that gentle soul that would just go that extra mile to help you. In the pit, I don’t know how the pit is these days, but he had command of everyone, and it was always an [laugh] experience. Kind of tried to stay out of the way [laugh]… and then when he was with the orchestra, the Oklahoma Symphony, the favorite story is… I don’t know if I should tell you this, but it’s hysterical. I know you don’t have to print it.

K: We can turn off the recording [laugh]

© 2019 Jake Johnson

The archive contains recordings of performances beginning in the early 1960s including recitals, major ensemble concerts, music theatre productions, faculty artist concerts, Project-21 concerts, and more. All of these concerts have been recorded on reel-to-reels, cassette tapes, and compact discs which take special equipment in order to play back the recordings.

As of the Spring of 2019, there are 3,639 recordings listed in the OKCU archives dating from 1963 to 2010. The majority of archival recordings are available on reel-to-reel cassettes and CDs. Of the 3,639 listings, there were 1,206 reel-to-reel tapes dating from 1963 to 1986, 673 cassettes dating from 1986 to 1997, and 1,760 CDs dating from 1997 to 2010. The OCU University Symphony started in 1937, but the earliest recording is from 1963 (T661963-1964 OKCU Concert Band). The first recording of the Symphony Orchestra on CD was made in 1998.

One goal we had in trying to process the entire collection of OCU University’s recordings was to determine the common performance canon of the OKCUSO. We studied programs ranging from 1937 to 2006. Although we were unable to find program information from the 1990s, we surmise that the canon largely consists of canonic composers such as Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms. The most frequently performed pieces are listed below:

Brahms, Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a (1968, 1973, 1979, 1982)

Beethoven, Egmont Overture (1978, 1982, 1985)

Debussy, Fetes (from ‚ÄúThree Nocturnes‚ÄĚ) (1968, 1975, 1982)

MacDowell, Piano Concerto in D Minor, Op. 23 (1937, 1944, 1949)

Mozart, Concerto for Clarinet K. 622 (1953, 1975, 1978)

Mussorgsky, Pictures at an Exhibition (1967, 1977, 1986)

Rimsky-Korsakov, La Grande Paque Russe (Russian Easter) (1973, 1979, 1984)

Shostakovich, Festival Overture (1968, 1972, 1982)

© 2019 Jake Johnson

Ray Luke was an American composer and conductor born in Fort Worth, Texas on May 20 of 1928. After receiving both a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree from Texas Christian University, Ray Luke taught for a short time at Atlantic Christian College and then at East Texas State College. After teaching at East Texas State for thirteen years, Luke attended Rochester University’s Eastman School of Music in 1957, and in 1960 received a doctorate in Music Composition.

In 1962, Dr. Luke joined the faculty at OCU University, where he was appointed Chairman of the Instrumental Music Department and also the Head of the Music Composition Department. He remained the chair of instrumental music until 1987 and the head of music composition until 1997. A year later, Dr. Luke was appointed as the director of the newly created Lyric Theatre (1963-1967) and in 1968 became the associate conductor of the OKC Symphony Orchestra (now known as the OKC Philharmonic). During Guy Fraser Harrison’s retirement in 1973, Ray Luke served as the interim conductor of the orchestra.

His career in composition spans forty-nine years between 1957 and 2006 totaling eighty-four works composed for orchestra, concert band, choir, solo instruments, chamber ensembles, opera, and ballet. The OKC Symphony Orchestra, under the direction of Guy Fraser Harrison, premiered many of his orchestral works, while the band at OCU University premiered many of the Concert Band works.

Many of his works received national and international acclaim, including his Concerto for Piano and Orchestra and his Medea Opera in Two Acts. Luke’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra won the top prize of the Queen of Belgium competition in 1969 and was performed in Europe by Claude-Albert Coppens. Luke’s Medea Opera in Two Acts won the New England Conservatory Opera Competition Award in 1979 where Luke later conducted the world premiere. Dr. Luke received several other accolades including the Oklahoma Musician of the Year (1970), Distinguished Alumnus of TCU (1972), the Oklahoma Governor’s Arts Award (1979), and more than 25 consecutive years of American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers Awards.

© 2019 Jake Johnson

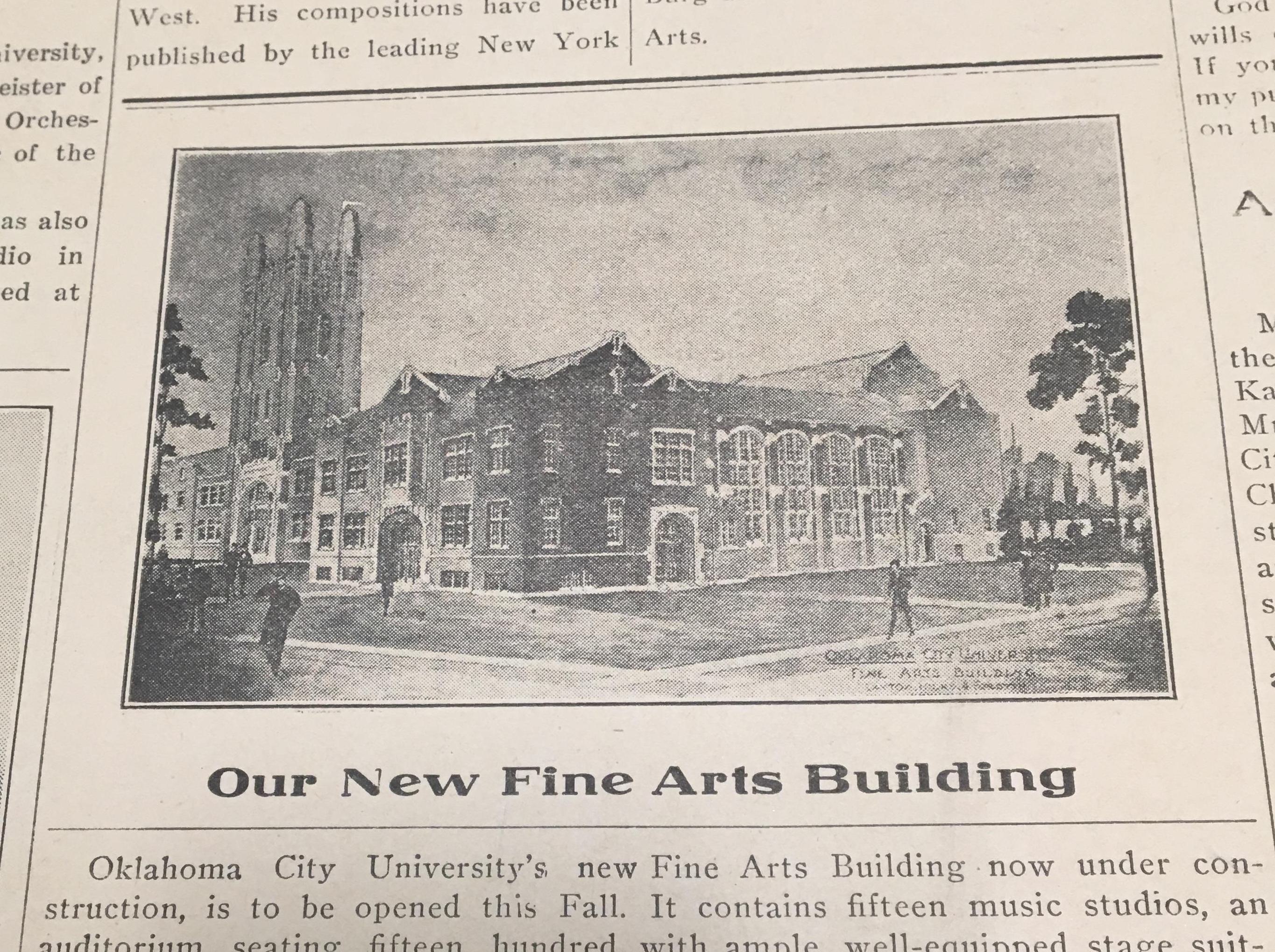

The Fine Arts building on campus at OCU University has a rich and full history. During the summer of 1922, the music program moved into the new administration building, located in the basement. That same year, the music department became part of the College of Fine Arts, and it became apparent that the music program was going to need a larger space. Six years later in 1928, construction began on the first Fine Arts building located at Blackwelder and 25th street.

The building opened for use in 1929 containing eighteen professor studios, a small theatre, and an auditorium with one thousand and four hundred seats (later named the Kirkpatrick Auditorium in 1967). The building was very modern for its time and helped the program to flourish. Many of the studios were rented out, and many of the classrooms hosted university clubs. Since then, OKCU has built several additions to the music campus including Petree Recital Hall, the Burg Auditorium, and the Wanda L. Bass Music Center. In 2006, the Bass Music Center officially opened to students. It provides an additional sixty practice rooms, forty teaching studios, music labs, and rehearsal halls. Over the years, the School of Music has been expanded, each time allowing the program to grow and evolve.

© 2019 Jake Johnson

J. Gerald Mraz (1874-1952) was one of the earliest violin instructors at OCU University. Mraz was a high-profile violinist dedicated to advancing violin pedagogy. Born in Iowa shortly after the American Civil War to Czech parents, Mraz attended Chicago Musical College before traveling to Europe to study at the Conservatory of Music in Prague, where he performed in an orchestra led by Czech conductor and composer, Anton√≠n DvoŇô√°k. While in Europe, Mraz also performed in an orchestra under the direction of Richard Strauss.

By the year 1920, Mraz made a home for himself in –Ŗ–Ŗ ”∆Ķ and founded the Mraz Violin School. He taught at OCU University from 1924 to 1927, and before the founding of OKCU, Mraz was involved in teaching violin at the University‚Äôs predecessor, Epworth University.

Mraz contributed two works to the field of violin pedagogy, Systematized Intervals (1909) and The Art of Violin Bowing (1927). These works were both serialized in the publication, The Violinist and were standard repertoire for many students of violin around the world. J. Gerald Mraz’s legacy at OCU University continued beyond his departure in 1927. One of his student’s, Mazo Pickle, the first person to earn a degree in violin from OCU University, became the new violin instructor. It was during this period of the history that the University began the process of forming an orchestra.

© 2019 Jake Johnson

The OCU University Symphony Orchestra is intrinsically linked to the history of the Epworth College Band. The college band was established in 1906 and was intended to be self-sufficient through regular performances and concerts. Epworth University’s Orchestra was not organized until 1924, with R.A.Weeks as manager and H.E. Brill as director. There were only seventeen members in the orchestra at Epworth. In 1936-1937 school year, James Neilson organized the OCU University Symphony Orchestra under Dean Clarence Burg’s direction. There were sixty players in the Symphony Orchestra, as required by James Neilson.

The OKCUSO‚Äôs first concert took place on May 5 of 1937 in the Fine Arts Auditorium. The performance was divided into two halves. In the first half, the ensemble performed W. A. Mozart‚Äôs Overture to Cosi fan tutte: Andante and Presto and Franz Schubert‚Äôs unfinished symphony, Symphony in B minor, conducted by Dean Clarence Burg. After the intermission, James Neilson replaced Dean Clarence Burg, who then performed Edward MacDowell‚Äôs Piano Concerto in D minor, Op. 23, as the conductor. The next piece was Saint-Saens‚Äô Bacchanale from the opera ‚ÄúSamson and Delilah.‚ÄĚ Finally, the orchestra played Tchaikovsky‚Äôs Marche Slave. Burg served not only as a conductor, but as a soloist.

The orchestra management announced future programs of the symphony orchestra for the 1937-38 season as a series of three programs containing such esteemed works as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Mozart’s Magic Flute Overture, Weber’s Der Freischutz Overture, Schubert’s Ballet Music from Rosamunde, Dvorak’s Carnival Overture, and Wagner’s Introduction to the Third Act of Lohengrin and Tannhauser Overture.

At its beginning, the OKCUSO was open to all students and professional musicians, additionally offering private and class instruction for orchestral instruments. The creation of the OCU University Symphony Orchestra was a decision that is still benefiting students 82 years later.

© 2019 Jake Johnson

When we got started in the archives, we were excited to have the entire catalogue of Dr. Ray Luke’s scores available for perusal. There were also two large folders with newspaper clippings all related to Ray Luke and his career in composition and conducting, including a couple of interviews. However, as we dove into these resources, we began to hit some roadblocks. The recordings that were catalogued and listed were not available in the library as listed, and while archivist Christina Wolf did find them for us, it was not until the end of our time on this project. We attempted to interview current faculty members here at OKCU who knew or were familiar with Luke, but we were mostly unsuccessful in gathering satisfying answers to our questions about Dr. Luke and his time at OKCU. There were some challenges to starting this research project, but we are mostly satisfied with how our research ended.

įŕ‚Ķ]

I tried to listen to an old reel-to-reel tape in the archive, but the sound was very unclear; I could hear a voice with some clarity, but the sound of instruments was not apparent. The reel-to-reel player is difficult to use, and the more modern recordings have much better sound quality. It would be nice if more of the archival holdings were available on CD‚Äďcassettes and reel-to-reel tapes will only continue to degrade and digital recordings are much more accessible.

įŕ‚Ķ]

The Recordings group had a bit of a slow start delving into this project. We were not able to access recordings or information regarding the recordings for a couple of class periods, so we temporarily merged with the group focusing on history. It was very exciting to look through so many OKCU newspapers from the 1920s and 1930s, although most of what we found did not pertain to the project at hand. We were eventually able to shift our attention back to the recordings when we obtained a list of the available recordings for the entire School of Music. Many of the reel boxes and CDs contained programs that were not catalogued, so the Programs group had not come across them in their research.

© 2019 Jake Johnson

Love what you see? Want to study music?

Be a part of the magic, and audition for the Wanda L. Bass School of Music!

Start your journey and apply today.